Logical Troubleshooting

The US Navy teaches a method of figuring out what is wrong with something that is "broken;" it is called Logical Troubleshooting.

It has been my experience that "technicians" who have not been educated in Logical Troubleshooting tend to "throw parts" at a problem, hoping one will solve the problem. Of course, if they do solve the problem, the Technician usually does not have a clue as to what failed, and more importantly, why something failed. Keeping a log or records concerning failure-events rarely enters their mind.

Successful at Logical Troubleshooting requires the Technician (and I use Technician to mean “someone that works with technical-things,” makes no difference whether GED or Ph.D.), the following are required:

- Absolute knowledge of what the system is doing vs what it should be doing

- A comfortable understanding of the technologies that comprise the system that could create a failure

- Comfortable interaction with the Operator

Unfortunately for the Technician, most systems are made up of some combination of electrical/ electronic pieces, mechanical sections and sometimes pneumatics, hydraulics and vacuum. To make things really interesting, many manufacturers of equipment throw in controllers and PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers).

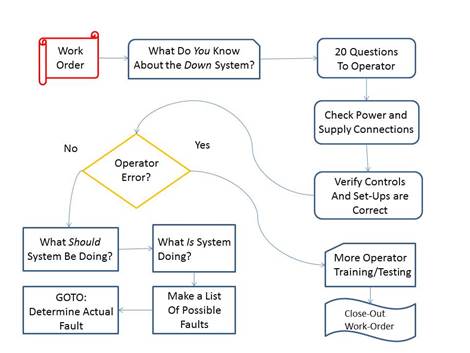

Figure 1

The Work Order - The first step is to understand what the work order (W/O) is asking of you, or in reality, what is the owner of the broken system asking you?

Many times the owner (or operator) is either clueless or lazy when it comes to filling out the W/O. How many times, the only words on the chit are "broken" or "doesn't work?" Here education is the best tool. If Leadership will support you, then take the W/O back to its originator and say, "When you fill this out correctly, telling me what the problem is, then I'll fix it."

I once received a W/O that said: "Broken. Emits dead-fish odor." This actually sets you in the right direction, but even if it smells funny, what is broken? It won't turn on? It makes a bad grinding noise? The lights in the entire bay dim-out when it's switched on? Anything that will take you off the wild goose chase and set you on the Yellow Brick Road to full production.

What Do You Know About the Down System? - Do you know how to turn this device ON? Do you know what it is supposed to do, how it functions correctly? Could you operate it in pace of its owner? If you do not have a really good understanding of a particular machine, take someone with you who understands the machine to work. If this is not possible, try to get an idea of what it is doing from the Operator vs. what it should be doing then return to a quiet place with the service manual. It is an Absolute Imperative that the person fixing a device knows how to work the device!

20 Questions to the Operator - Sometimes talking to the Operator can solve the entire problem. Power-Down the entire system (including ancillaries like vacuum, air, gasses etc.) Start the system and have them walk you through what they did to allowed them to discover a fault. Sometimes they overlook a setting, and going through it with you, she does everything right, and Voilà, it works! Close the W/O. If not, the more information you have about the failure, the easier it is to narrow-down the fault.

Check Power and Supply Connections - Whilst you are having the conversation with the Operator, make sure it has a good power-connection and that the gasses, steam, vacuum and any other external requirements are available. Things like raw-materials and supplies count here too. I cannot tell you how many times the lab-instrument was unplugged (behind the device) or the vacuum-line valve was off! Plug it in, turn it on and it works like a charm. It's better to check these things out first than tearing the machine apart only to find it was out of paper!

Check Controls and Set-Ups - Just like power, some machines won't run if the controls or the raw materials are set-up just right. Think in terms of a photocopier or a printer: it takes very little error in alignment of the paper-supply to stop the machine from functioning.

Operator Error? - It is the easiest of fixes, albeit the most embarrassing for the Operator. Better this way than to spend a week only to find the vacuum was turned off!

The other important thing here is educating the Operator; not only will you not waste time, production won't suffer.

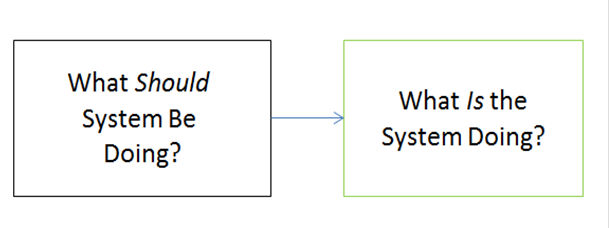

What Should the System Be Doing vs. What Is the System Doing? - Herein lays the answer to how to fix the fault.

Figure 2

This is the point where either you, the Operator or a colleague understands exactly how the machine should be performing.

A simple mathematical formula:

(The Expected Operation) - (How It Is Operating In Front of You) = The Problem

Example 1:

Example 1:

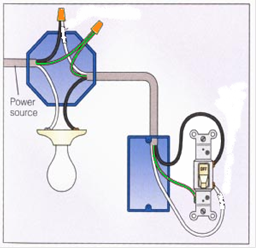

- The Power Switch is flipped ON

- The Light does not illuminate

Troubleshoot Logically

- What should the system be doing?

- The light should illuminate.

- Since Light Bulbs fail on a regular basis, change the bulb.

- Light comes ON, job done!

![]() Being very simplistic, let’s take this to the next level:

Being very simplistic, let’s take this to the next level:

The lightbulb has been replaced and it still does not work

- Are you sure the replacement is good? Taking it from a stash on brand-new bulbs is not a guarantee that it will work.

- Go someplace where a lightbulb is working and try the new bulb there. If it glows, then the problem is elsewhere. It is important to rule-out an many variables as possible, until you are at the last possible variable

- Figure 1 says to first verify the power supply

- In this case it is most likely a Circuit Breaker; is it tripped?

- If tripped, RESET and see what happens

- If the bulb lights and stays lit, problem solved

- I would like to know why the breaker tripped

- If it trips again, you need to determine what else is powered from this breaker and fix that

- Sometimes, but rarely, breakers fail and trip just to piss you off. . .

- If the Breaker is RESET and stays RESET, but the bulb still won’t light,

- Ask yourself the question: What else is in the path of current flow that will interrupt flow in this circuit?

- The Power Switch (and they certainly do fail!)

- Replace Switch and try again

- Works fine; go have a coffee to celebrate

This may seem like a lot of trouble, but if you are working on an automated packaging machine with thousands or parts, many different inputs and a PLC, this process will not only simplify the repair, keep costs to a minimum, and be expeditious as well.

A Technician could solve this problem with minimal training in the Electrical Arts, however, I cannot stress, the more you understand a field, the more quickly you can solve a problem.

Let’s go back to 3b above: the Switch is replaced, but still no light. You “ring out” the switch with an Ohmmeter and it is good. The Bulb is good; there is 120v across the lamp. What can it be?

Stop here and think about it; don’t peek. . .

A multimeter requires μA to function; an analog-type meter, maybe a couple of mA to deflect the needle to where it should be. If there is any corrosion between the terminals and the wires (especially if the wire is Al and the terminal is Cu) then the hundreds of mA that the lamp is drawing will be dropped across the terminal corrosion – which is effectively a resistor! Even though you are reading voltage at the light-socket and the bulb is good, the voltage will be dropped across the terminals.

Knowledge is Power

The more you know about how things work, the easier it becomes to figure out what is causing them to fail.

Many electrical systems can be viewed or modeled as hydraulic systems. If you have this basic knowledge, moving onward to pneumatics, hydraulics, vacuum and refrigeration is a matter of terminology.

More to follow. . .